Time-travelling billiard balls#

For a spacetime with one or more chronology-violating sets (regions containing CTCs), the past can be influenced by the future, provided that any changes which are made obey the self-consistency principle. The lack of such changes (e.g., self-interactions) in the Cauchy problem for non-interacting classical fields seems like a probable cause of its well-posedness on CTC spacetimes. Alternatively, a system that is able to self-interact (e.g., collide with its past/future self) is more likely to display unusual results—indeed, with an interacting field, uniqueness is thought to be lost as the strength of the interaction increases [3]. Therefore, in order to study this, models of interacting systems near CTCs were developed, and perhaps the most famous of these considers the elastic self-collision(s) of a time-travelling billiard ball. In this framework, a solid, elastic, spherical mass (the billiard ball) enters one mouth of a wormhole-based time machine, exits the other at an earlier time (due to a time-shift having been induced between the wormhole’s two mouths), and then collides with its earlier (past) self. Depending on the initial position and velocity of the ball, drastically distinct evolutions of the ball through the CTC-wormhole region can arise.

Indeterministic dynamics and evolution multiplicity#

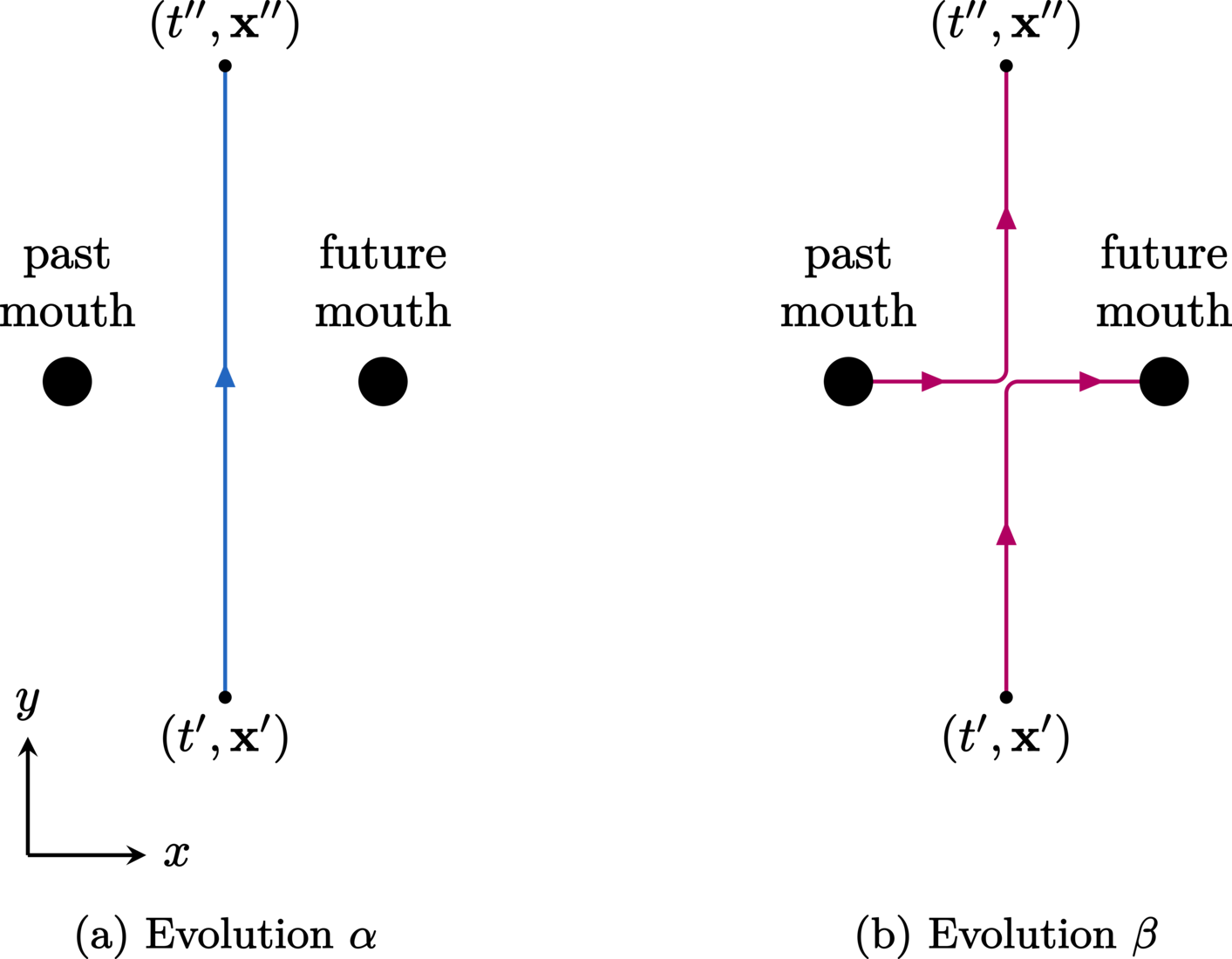

Studies [2, 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] involving time-travelling billiard balls have shown that, given the same initial data posed in the presence of CTCs, there can be multiple self-consistent solutions which satisfy the equations of motion. Figure 3 illustrates a prominent example in which there are (at least) two distinct histories through which the billiard ball may evolve in a CTC-wormhole spacetime. This scenario is the foremost example of the billiard-ball paradox, and will hereafter be referred to as such. It is important to note that while the motivating formulation of this problem explicitly involves a wormhole-based time machine, the essence of the paradox is contingent only on the presence of CTCs that exactly facilitate the required function. In other words, while wormhole-based time machines make for perhaps the simplest conceptual model of CTCs, the physical mechanism behind the antichronological time travel in the billiard-ball paradox is irrelevant.

Unlike in the case of the grandfather paradox, the paradoxical issue here is not of self-inconsistent trajectories but is of the indeterminism in the self-consistent ones. This is to say that solutions always exist because they self-adjust themselves (thereby providing consistency), but we now have a different issue, that of solution multiplicity. This new problem is an interesting one, as the existence of more than one solution to the equations of motion contrasts with the determinism typically associated with classical mechanics.

Quantum resolutions to classical indeterminism#

It is natural to question whether the characteristic of solution multiplicity is indeed merely an artefact of a classical description and vanishes in a fully self-consistent quantum mechanical treatment, or whether it remains as a pathological aspect of CTCs and time travel under any physical description. In past work [2], it has been suggested that the indeterminism problem of the billiard-ball paradox disappears in quantum theory. The reasoning behind this is that, unlike classical mechanics, a quantum treatment provides one with ways of assigning solution probabilities, thereby replacing the classical theory’s multiplicity of solutions with a set of probabilities for the outcomes of all sets of measurements.

For example, a quantum prescription based on the path-integral formulation tells us that classical trajectories coexist in a probabilistic sense. In a prominent paper by Friedman et al. [2], the authors discuss such a prescription applied to the exact evolutions depicted in Figure 3. When the ball begins in a nearly classical wave-packet, Friedman et al. postulate that a WKB (Wentzel-Kramers-Brioullin) approximation to their sum-over-histories method would find that the wave-packet emerges from the CTC-wormhole region having travelled along either evolution \(\EvolutionNoninteracting\) or \(\EvolutionInteracting\) with equal (i.e., \(50\%\)) probability. One interpretation of this is to say that the associated quantum billiard ball travels along both paths simultaneously through the time-machine region, thus ameliorating the indeterminism of classical mechanics. However, no calculation is provided in [2] or any subsequent papers to support the WKB approximation conjecture. Nonetheless, the pioneering semiclassical method proposed by Friedman et al. motivates further study of this problem, as the interesting probabilistic result they postulated is simply inaccessible to classical mechanics.

References

A. S. Lossev and I. D. Novikov, “The jinn of the time machine: nontrivial self-consistent solutions”, Classical and Quantum Gravity, 9(10):2309, 1992. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0264-9381/9/10/014, doi:10.1088/0264-9381/9/10/014

J. Friedman, M. S. Morris, I. D. Novikov, F. Echeverria, G. Klinkhammer, K. S. Thorne, and U. Yurtsever, “Cauchy problem in spacetimes with closed timelike curves”, Physical Review D, 42(6):1915–1930, September 1990. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.42.1915, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.42.1915

J. L. Friedman, “The Cauchy Problem on Spacetimes That Are Not Globally Hyperbolic”, The Einstein Equations and the Large Scale Behavior of Gravitational Fields, pages 331–346, Birkhäuser, Basel, 2004. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-0348-7953-8_9, doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-7953-8_9

F. Echeverria, G. Klinkhammer, and K. S. Thorne, “Billiard balls in wormhole spacetimes with closed timelike curves: Classical theory”, Physical Review D, 44(4):1077–1099, August 1991. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.44.1077, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.44.1077

I. D. Novikov, “Time machine and self-consistent evolution in problems with self-interaction”, Physical Review D, 45(6):1989–1994, March 1992. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.45.1989, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.45.1989

E. V. Mikheeva and I. D. Novikov, “Inelastic billiard ball in a spacetime with a time machine”, Physical Review D, 47(4):1432–1436, February 1993. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.47.1432, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.47.1432

M. B. Mensky and I. D. Novikov, “Three-dimensional billiards with time machine”, International Journal of Modern Physics D, 05(02):179–192, April 1996. https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/10.1142/S0218271896000126, doi:10.1142/S0218271896000126

J. Dolanský and P. Krtouš, “Billiard ball in the space with a time machine”, Physical Review D, 82(12):124056, December 2010. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevD.82.124056, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.82.124056