Grandfather paradox#

Description#

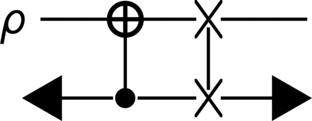

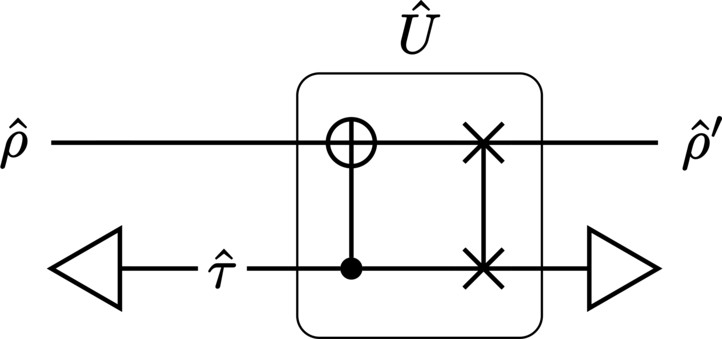

Probably the most prominent time-travel paradox is the grandfather paradox. Presented here is a simplified, quantum version of the paradox (based on [4]), in which a qubit CV state has an apparently paradoxical influence on its past self (exterior to the CTC) via a CNOT operation. This is illustrated in Figure 27.

It consists of two systems: the first (upper) is the chronology-respecting (CR) system, while the second (lower) is the chronology-violating (CV) one. The Hilbert spaces of both will be ordinary qubit spaces, and using these we wish to describes the propagation of an observer (who can be either alive or dead) through the time machine and its chronology-violating region. Without loss of generality, we arbitrarily associate the level \(\ket{0}\) with observer’s state of being dead, while \(\ket{1}\) will denote their alive state. The circuit therefore describes the propagation of an observer whose state changes in accordance with their future state in the time machine (due to the CNOT gate), after which they SWAP onto the CV system and experience the interaction from the other perspective. The combined unitary gate thus has the form

As this is a quantum temporal paradox, there are multiple prescriptions by which resolutions can be computed.

Solutions#

D-CTCs#

In Deutsch’s model (D-CTCs), we necessarily have to calculate fixed-point solutions \(\StateCV\) for the CV system. This is accomplished by first computing the standard evolution of the bipartite input state \(\StateCR \otimes \StateCV\),

Subsequently tracing out the CR system yields the D-CTCs CV map,

while tracing out the CV system gives the CR map,

Solutions for the CV system are then given as fixed points of the corresponding map, i.e. \(\StateCV_\MapDCTCsCR = \MapDCTCsCV_{\Unitary} \bigl[\StateCR,\StateCV_\MapDCTCsCR\bigr]\), and accordingly we find the unique state

With this, the solution for the CR system can be computed to be

which is similarly unique.

P-CTCs#

To compute the resolution to the grandfather paradox according to the postselected teleportation (P-CTCs) prescription of quantum time travel, we first calculate the reduced P-CTC operator,

Using this, we can obtain the P-CTC CR state from its definition (252),

where we have used the canonical form

Finally, using the expression (255), we can compute the P-CTC CV state (via weak-measurement quantum state tomography) to be

Note that this is identical to the D-CTC CV state (380).

P-CTC restrictions on initial data#

The grandfather paradox is particularly interesting because it exhibits pathological behaviour under the P-CTC prescription. Indeed, its antichronological effect on a general qubit can be observed by analyzing the evolution of the entangled state,

where \(0 \leq \Omega \leq 1\) controls the balance of the entanglement. Here, the first subsystem is the record subsystem which, due to the entanglement, tells us (after measurement) which CR state interacted with the P-CTC. Accordingly, by using the bipartite unitary

where \(\OperatorPCTC = \trace_\CV[\Unitary]\) is the P-CTC operator, we obtain the evolution

Renormalization vanishes the coefficient \(\sqrt{2\Omega}\), leaving the record to consist of only the state \(\ket{0}\) regardless of the value of \(\Omega\). This suggests that the CR input was likewise only \(\ket{0}\) even if \(\Omega \neq 1\), indicating that the entanglement was broken.

Prior to the renormalization, a value of \(\Omega = 0\) leads to a vanishing P-CTC evolution, and so the renormalization process merely serves to produce a physical output state for all \(\Omega\). In doing so however, the record reveals that a CR input of \(\ket{1}\) was never prepared, even when \(\Omega \neq 1\). An input of \(\StateCR = \ket{1}\bra{1}\) is thus forbidden under the P-CTC description of this simplified grandfather paradox. With the interpretation of \(\ket{1}\) as corresponding to “alive”, this result is curious, but is probably just an indication that this particular version of the grandfather paradox is overly simplistic. Additionally, in practice, the effects of quantum noise and decoherence would ensure that such an exact input state is not physically realizable. In any case, we conclude that although the grandfather paradox’s interaction places theoretical constraints for certain input CR states, a (unique) P-CTC CV state \(\StateCV_{\MapPCTCsCR}\) can always be determined via (255).

Implementation#

from qhronology.quantum.states import MixedState

from qhronology.quantum.gates import Not, Swap

from qhronology.quantum.prescriptions import QuantumCTC, DCTC, PCTC

import sympy as sp

# Input

rho = sp.MatrixSymbol("ρ", 2, 2).as_mutable()

input_state = MixedState(spec=rho, conditions=[(rho[0, 0], 1 - rho[1, 1])], label="ρ")

# Gates

NC = Not(targets=[0], controls=[1], num_systems=2)

S = Swap(targets=[0, 1], num_systems=2)

# CTC

grandfather = QuantumCTC([input_state], gates=[NC, S], systems_respecting=[0])

grandfather.diagram()

# Output

# D-CTCs

grandfather_DCTC = DCTC(circuit=grandfather)

grandfather_DCTC_respecting = grandfather_DCTC.state_respecting(norm=False, label="ρ_D")

grandfather_DCTC_violating = grandfather_DCTC.state_violating(norm=False, label="τ_D")

grandfather_DCTC_respecting.apply(sp.factor)

# P-CTCs

grandfather_PCTC = PCTC(circuit=grandfather)

grandfather_PCTC_respecting = grandfather_PCTC.state_respecting(norm=1, label="ρ_P")

grandfather_PCTC_violating = grandfather_PCTC.state_violating(norm=1, label="τ_P")

grandfather_PCTC_respecting.coefficient("1/(sqrt(2))") # Manually renormalize

grandfather_PCTC_respecting.simplify()

grandfather_PCTC_violating.simplify()

# Results

grandfather_DCTC_respecting.print()

grandfather_DCTC_violating.print()

grandfather_PCTC_respecting.print()

grandfather_PCTC_violating.print()

Output#

Diagram#

>>> grandfather.diagram()

States#

>>> grandfather_DCTC_respecting.print()

ρ_D = 1/2|0⟩⟨0| + (ρ[0, 1] + ρ[1, 0])**2/2|0⟩⟨1| + (ρ[0, 1] + ρ[1, 0])**2/2|1⟩⟨0| + 1/2|1⟩⟨1|

>>> grandfather_DCTC_violating.print()

τ_D = 1/2|0⟩⟨0| + (ρ[0, 1]/2 + ρ[1, 0]/2)|0⟩⟨1| + (ρ[0, 1]/2 + ρ[1, 0]/2)|1⟩⟨0| + 1/2|1⟩⟨1|

>>> grandfather_PCTC_respecting.print()

ρ_P = 1/2|0⟩⟨0| + 1/2|0⟩⟨1| + 1/2|1⟩⟨0| + 1/2|1⟩⟨1|

>>> grandfather_PCTC_violating.print()

τ_P = 1/2|0⟩⟨0| + (ρ[0, 1]/2 + ρ[1, 0]/2)|0⟩⟨1| + (ρ[0, 1]/2 + ρ[1, 0]/2)|1⟩⟨0| + 1/2|1⟩⟨1|

References

S. Lloyd, L. Maccone, R. Garcia-Patron, V. Giovannetti, Y. Shikano, S. Pirandola, L. A. Rozema, A. Darabi, Y. Soudagar, L. K. Shalm, and A. M. Steinberg, “Closed Timelike Curves via Postselection: Theory and Experimental Test of Consistency”, Physical Review Letters, 106(4):040403, January 2011. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.040403, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.040403